Imagine waking up one morning and finding out the price of a gallon of milk has plummeted to just a few cents. While this might sound like a dream come true for consumers, for farmers struggling to make ends meet, this scenario could spell disaster. This seemingly paradoxical situation, where the price of a product is so low it threatens the very existence of its producers, is the crux of the problem that price floors aim to solve. But why are these laws, often seen as controversial, put into place?

Image: www.chegg.com

A price floor is a government-mandated minimum price for a good or service. It’s like a safety net, preventing the price from falling below a certain level. While this concept might appear straightforward on the surface, its practical implications can be complex and far-reaching, affecting not just producers but also consumers, the overall market, and even the government itself. But before we delve into the intricacies of price floors, let’s first understand why they are deemed necessary in the first place.

The Rationale Behind Price Floors

Protecting Producers:

The primary objective of a price floor is to protect the income of producers, particularly those operating in industries considered essential, such as agriculture. When market forces drive prices down, producers struggle to cover their production costs, leading to potential losses and, in extreme cases, even business failure. A price floor, by setting a minimum price, aims to ensure that producers receive a fair income, allowing them to continue operating and supplying the market with needed goods.

Take, for instance, the dairy industry. Due to factors like oversupply, fluctuating demand, and increased competition, milk prices can fluctuate dramatically, often falling below profitable levels for dairy farmers. A price floor, in this case, would set a minimum price that dairy farmers are guaranteed to receive, regardless of market fluctuations. This ensures their continued ability to produce milk, safeguarding food security and preventing potential shortages.

Promoting Stability:

Price floors are also designed to stabilize markets by preventing sudden price drops that could have far-reaching consequences. Sharp price fluctuations can disrupt supply chains, discourage investment in production, and lead to market instability. By setting a minimum price, a price floor acts as a buffer, minimizing dramatic market swings and fostering a more predictable and reliable market environment.

Consider the impact of a sudden drop in the price of wheat. This could disincentivize farmers from planting wheat in the future, fearing low profits. This could lead to shortages in the following year, driving wheat prices even higher, potentially triggering a cycle of instability. A price floor, by setting a minimum price for wheat, would counter this instability, encouraging farmers to continue production, ensuring a steady supply, and mitigating drastic price fluctuations.

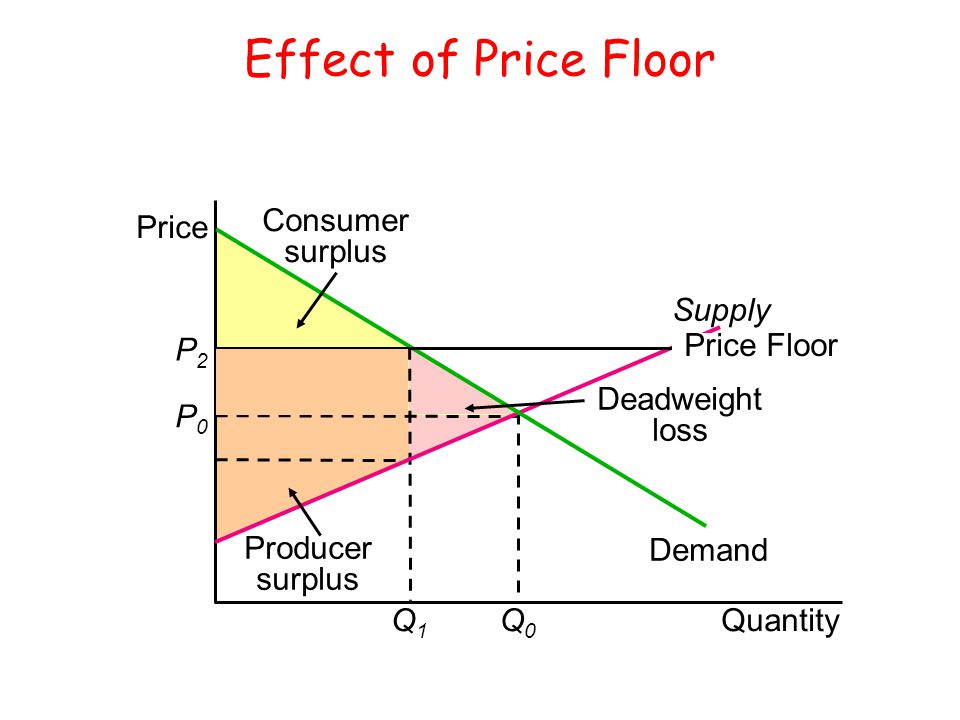

Image: www.gemanalyst.com

Ensuring Quality:

While not always the primary objective, price floors can also promote the production of higher quality goods. Since producers are guaranteed a minimum income, they can afford to invest in better quality inputs, improved production methods, and higher quality control measures. This benefit is particularly important in industries where quality is paramount, such as agriculture and manufacturing.

Imagine a scenario where farmers are forced to produce lower quality crops due to low prices, simply to make ends meet. A price floor, by ensuring a minimum income, enables them to invest in better seeds, improved fertilization techniques, and more efficient harvesting methods. This translates to higher quality produce, potentially benefitting consumers in the long run.

The Limitations and Criticisms of Price Floors

While price floors might address certain market imbalances, they are not without their limitations and criticisms. The most prominent of these include:

Surpluses and Waste:

One of the most significant drawbacks of price floors is the potential for creating surpluses. When prices are artificially raised above the equilibrium price, demand decreases as consumers become price-sensitive. Meanwhile, producers, encouraged by the higher prices, may increase production. This mismatch between supply and demand can lead to an accumulation of unsold goods, resulting in waste and potential economic losses.

Think about the classic example of minimum wage laws, which act as a price floor for labor. When the minimum wage is set above the equilibrium wage, businesses may hire fewer workers than they would otherwise, leading to unemployment. This unemployment can be seen as a form of “surplus” of labor, with individuals willing to work but unable to find jobs at the enforced minimum wage.

Black Markets:

Another potential consequence of price floors is the emergence of black markets. When the legal price of a good is artificially inflated, it creates an incentive for illegal trade at lower prices. This not only undermines the intended purpose of the price floor but can also lead to increased crime and social instability.

For example, in countries with price controls on essential goods like gasoline, black markets can flourish, with individuals buying gasoline at regulated prices and selling it illegally at higher prices. This not only deprives the government of tax revenue but can also lead to violence and corruption, as individuals compete for scarce resources.

Distortion of Market Signals:

Price floors distort the natural flow of market signals, disrupting the delicate balance between supply and demand. Prices act as signals, transmitting information about the relative scarcity and value of goods. When these signals are artificially manipulated, they can lead to misallocation of resources, inefficient production, and ultimately, economic inefficiency.

Consider the example of a price floor on agricultural products. When prices are artificially raised above market equilibrium, farmers may shift their production towards those subsidized goods, even if the market demand for those goods is lower. This misallocation of resources can lead to the production of excess goods with limited demand, ultimately creating waste and reducing overall efficiency.

Government Costs:

Price floors often require significant government intervention to enforce and sustain. The government may need to buy surplus goods to prevent prices from falling below the mandated minimum, which can lead to substantial financial burdens. Additionally, the government may need to regulate production and distribution to ensure compliance with the price floor, requiring substantial administrative resources and manpower.

For instance, if the government establishes a price floor for milk, they might need to purchase excess milk from dairy farmers to maintain the mandated price. This can be an expensive undertaking, requiring public funds and diverting resources from other social and economic priorities.

Real-World Examples and Historical Context

Price floors have been employed in various industries and economies throughout history, with varying degrees of success and drawbacks. Some prominent examples include:

The Minimum Wage:

One of the most widely known applications of price floors is the minimum wage, which acts as a minimum price for labor. The rationale behind minimum wages is to ensure that workers receive a living wage, protecting them from exploitation and poverty. However, debates rage on regarding the potential negative consequences, such as job losses and reduced employment opportunities, particularly in industries with low profit margins.

Agriculture Price Supports:

Many countries employ price support programs for agricultural products, often using price floors to ensure stable incomes for farmers and protect food security. These programs can involve direct payments to farmers, government purchases of surplus crops, or price guarantees. While these programs can buffer farmers from price volatility, they can also lead to inefficiencies and high government costs.

The US Sugar Program:

A prominent example of a price floor in action is the US sugar program. This program sets a minimum price for sugar through a system of quotas and import restrictions. This has maintained relatively high sugar prices in the US but has also resulted in higher costs for sugar consumers, as well as inefficiencies in the sugar industry, creating opportunities for black markets.

The Future of Price Floors

The use of price floors continues to be a complex and controversial issue, with ongoing debates about their effectiveness and potential consequences. As markets become increasingly globalized and subject to fluctuations in demand and supply, the need to address volatility and ensure producer incomes becomes more crucial. However, it is essential to weigh the potential benefits of price floors against their drawbacks, considering their impact on efficiency, innovation, consumer welfare, and overall economic well-being.

In the future, it is likely that more sophisticated and targeted policies will emerge, considering the specific characteristics and challenges of individual industries. This could involve combining price floors with other measures, such as agricultural subsidies, direct income support, or production quotas, to address specific market distortions while minimizing potential negative consequences. Additionally, there is growing interest in exploring alternative mechanisms for supporting producers, such as promoting sustainable agriculture, fostering innovation, and strengthening market access for small-scale producers.

Why Are Binding Price Floor Laws Passed

Conclusion

Price floors, while potentially helpful in tackling issues of market instability and producer income, are not a panacea. Understanding their limitations and potential consequences is crucial for policymakers and the public alike. The future of price floors lies in finding innovative and nuanced approaches that balance the need for market stability and producer protection with consumer welfare and economic efficiency. Continued dialogue and research are essential to ensure that price floor policies are tailored to specific contexts and effectively address the challenges of modern markets.