Imagine a world where education is deemed a tool of the “bourgeoisie,” where traditional arts are branded as “feudal relics,” and where children are encouraged to denounce their own parents for harboring “capitalist” tendencies. This was the reality of the Cultural Revolution, a period of profound social and political upheaval that gripped China from 1966 to 1976.

Image: www.nybooks.com

The Cultural Revolution, as its name suggests, aimed to reshape Chinese society in the image of Chairman Mao Zedong’s radical vision of communism. It was a fervent attempt to eliminate any remnants of traditional Chinese culture and institutions that stood in the way of a complete ideological transformation. This tumultuous period, marked by widespread chaos and violence, left an indelible mark on China, forever altering its social fabric and the course of its history.

The Genesis of a Revolution: Seeds of Discontent and a Call to Arms

The Red Guards: The Vanguard of a Cultural Revolution

While the Cultural Revolution officially began in 1966, its roots can be traced back to Mao Zedong’s concerns about the growing influence of “bourgeois” elements within the Communist Party. Mao, fearing a counter-revolution, launched the “Great Leap Forward” in 1958, a campaign aimed at rapidly industrializing China through collectivized agriculture. However, the campaign resulted in widespread famine and economic hardship, ultimately failing to achieve its objectives.

Mao Zedong, believing that the Party had diverged from his revolutionary ideals, sought to recapture control of the narrative. In 1966, he launched the Cultural Revolution, positioning it as a “proletarian revolution” against the “elitist” elements within the Party. The movement gained momentum with the formation of the Red Guards, a paramilitary youth organization that became the spearhead of the Cultural Revolution.

Composed of enthusiastic young people, the Red Guards were fueled by ideological zeal and a burning desire to “purify” Chinese society. They believed they were fighting for a noble cause, a belief that fueled their brutal campaigns against perceived enemies. Schools were shut down, universities were disrupted, and cultural institutions were desecrated, all in the name of purging the “poisonous” influence of traditional culture.

The Reign of Chaos: The Cultural Revolution in Action

Image: www.ar15.com

The Struggle Sessions: Public Humiliation and Repression

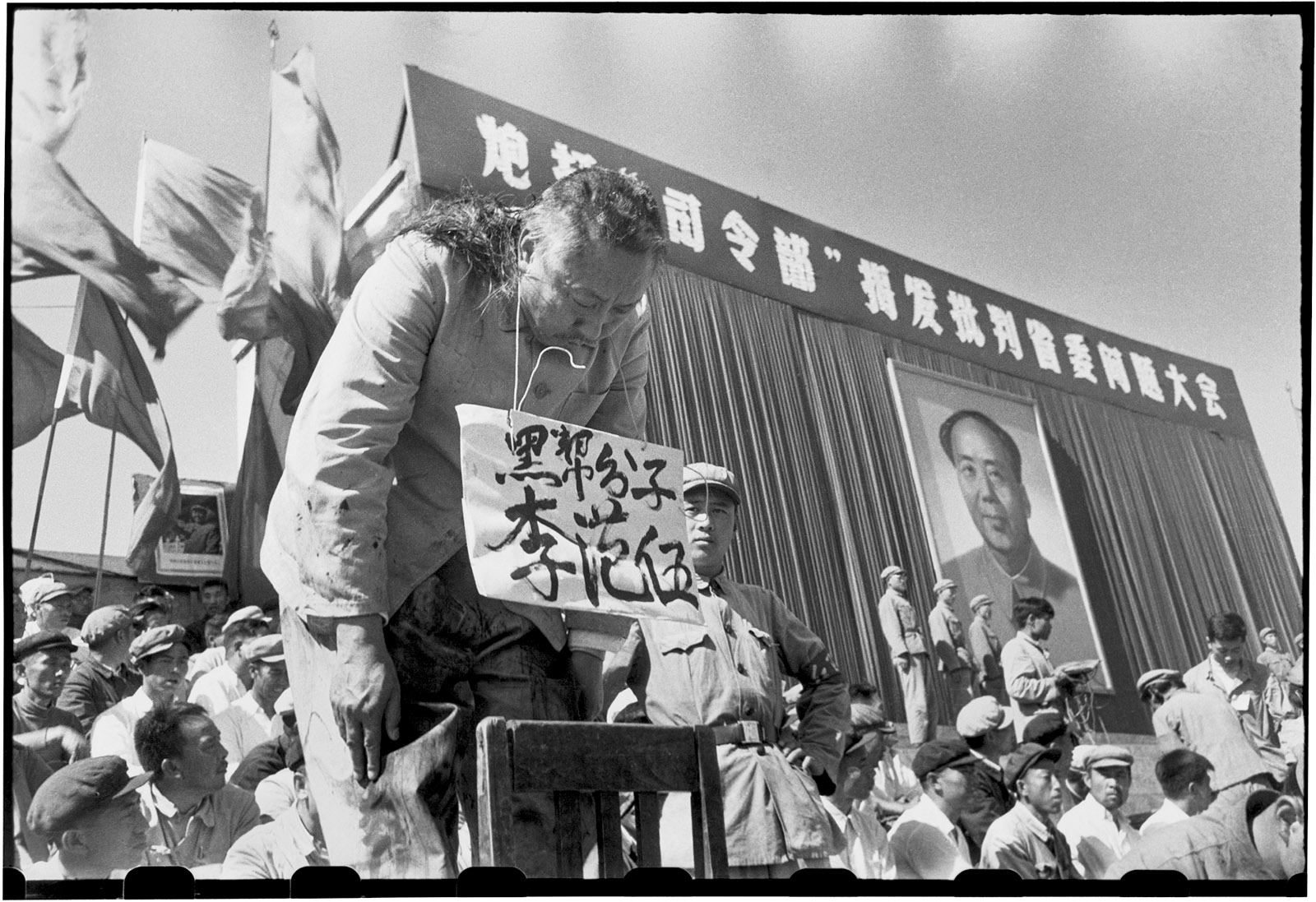

The Cultural Revolution was characterized by a climate of fear and paranoia. The Red Guards, armed with the power of Mao’s pronouncements and their own fervent beliefs, unleashed a series of campaigns that aimed to root out “counter-revolutionaries” and “capitalist roaders.” The most visible and terrifying manifestation of this campaign were the struggle sessions.

These public gatherings were designed to humiliate and punish those accused of political dissent or ideological deviation. Individuals were subjected to public criticism, physical abuse, and even forced confessions. The goal was to publicly expose and isolate those deemed a threat to the revolution. Ironically, the struggle sessions themselves became a symbol of the Cultural Revolution’s inherent brutality and the extent of its impact on Chinese society.

The Destruction of Cultural Heritage: Erasing the Past, Shaping the Future

The Cultural Revolution was more than just a political campaign; it was a determined attempt to eradicate traditional Chinese culture and replace it with a new ideology built around Mao Zedong’s thought. This involved a systematic destruction of cultural heritage, considered as a vestige of the “old” China. Temples, pagodas, and historical artifacts were ransacked and destroyed.

Confucianism, with its emphasis on social hierarchy and tradition, was declared a “feudal relic” and condemned. Traditional Chinese medicine, calligraphy, and opera were similarly targeted for their perceived association with the past. Libraries were looted and books considered “revisionist” were burned, effectively wiping out generations of knowledge and artistic creation.

The End of an Era: The Aftermath and Legacy of the Cultural Revolution

The Rise and Fall of the Gang of Four: The Revolution’s Ultimate Betrayal

The Cultural Revolution, despite its initial fervor, eventually imploded under the weight of its own excesses. The Red Guards, initially unified by their shared ideology, splintered into factions, leading to widespread chaos and violence. The movement, which began as a call for social purification, had become a vehicle for power struggles and factionalism.

In the aftermath of Mao Zedong’s death in 1976, a power struggle erupted between those who supported the Cultural Revolution and those who opposed it. Ultimately, the “Gang of Four,” a group of radical leaders who had risen to prominence during the Cultural Revolution, was purged from power. Their removal marked the end of the Cultural Revolution, although its ramifications continued to reverberate through Chinese society for years to come.

The Scars of a Revolution: Assessing the Legacy of the Cultural Revolution

The Cultural Revolution remains a controversial and complex period in Chinese history. While it initially sparked a sense of revolutionary fervor, it ultimately resulted in widespread suffering, destruction, and loss of life. Millions of people were persecuted, imprisoned, or even murdered in the name of the movement, and countless cultural treasures were lost.

The Cultural Revolution’s legacy is not just about the tangible damage it inflicted; it also raises questions about the dangers of unchecked political power and the consequences of revolutionary zeal taken to extremes. The movement serves as a stark reminder of the potential for ideological fervor to devolve into chaos and violence, reminding us of the importance of critical thinking and the preservation of individual freedoms and cultural heritage.

What Was The Cultural Revolution

Moving Forward: Lessons Learned and Ongoing Discourses

The Cultural Revolution is not simply a historical footnote; its repercussions continue to resonate in contemporary China. The country is still grappling with the scars of the period, and the movement continues to be a subject of debate and analysis. While the Cultural Revolution was a dark period in China’s history, it also offers valuable lessons about the dangers of extremism and the importance of maintaining balanced and tolerant perspectives.

The Cultural Revolution serves as a cautionary tale, reminding us that the pursuit of utopia or social engineering can often come at great costs. It underscores the need for open dialogue, respect for individual rights, and the preservation of cultural diversity. By studying this period in Chinese history, we can gain a deeper understanding of the complexities of social and political change and the importance of safeguarding human rights and cultural heritage.