Ever wondered why people in small, tight-knit communities seem to share a strong sense of belonging, while in bustling cities, individuals often find themselves adrift in a sea of anonymity? This fundamental difference in social cohesion lies at the heart of Émile Durkheim’s groundbreaking theory of social solidarity, a concept that explores the factors that bind individuals together in a society. Durkheim, a renowned sociologist, identified two primary forms of social solidarity: mechanical solidarity and organic solidarity, each reflecting distinctly different ways societies organize and function.

Image: helpfulprofessor.com

This article delves into these two crucial concepts, examining their distinct features, uncovering their historical roots, and exploring real-world examples that bring these abstract ideas to life. Understanding mechanical and organic solidarity provides a powerful lens through which to analyze social structures, understand cultural differences, and navigate the complexities of our interconnected world.

Mechanical Solidarity: The Glue of Shared Beliefs and Traditions

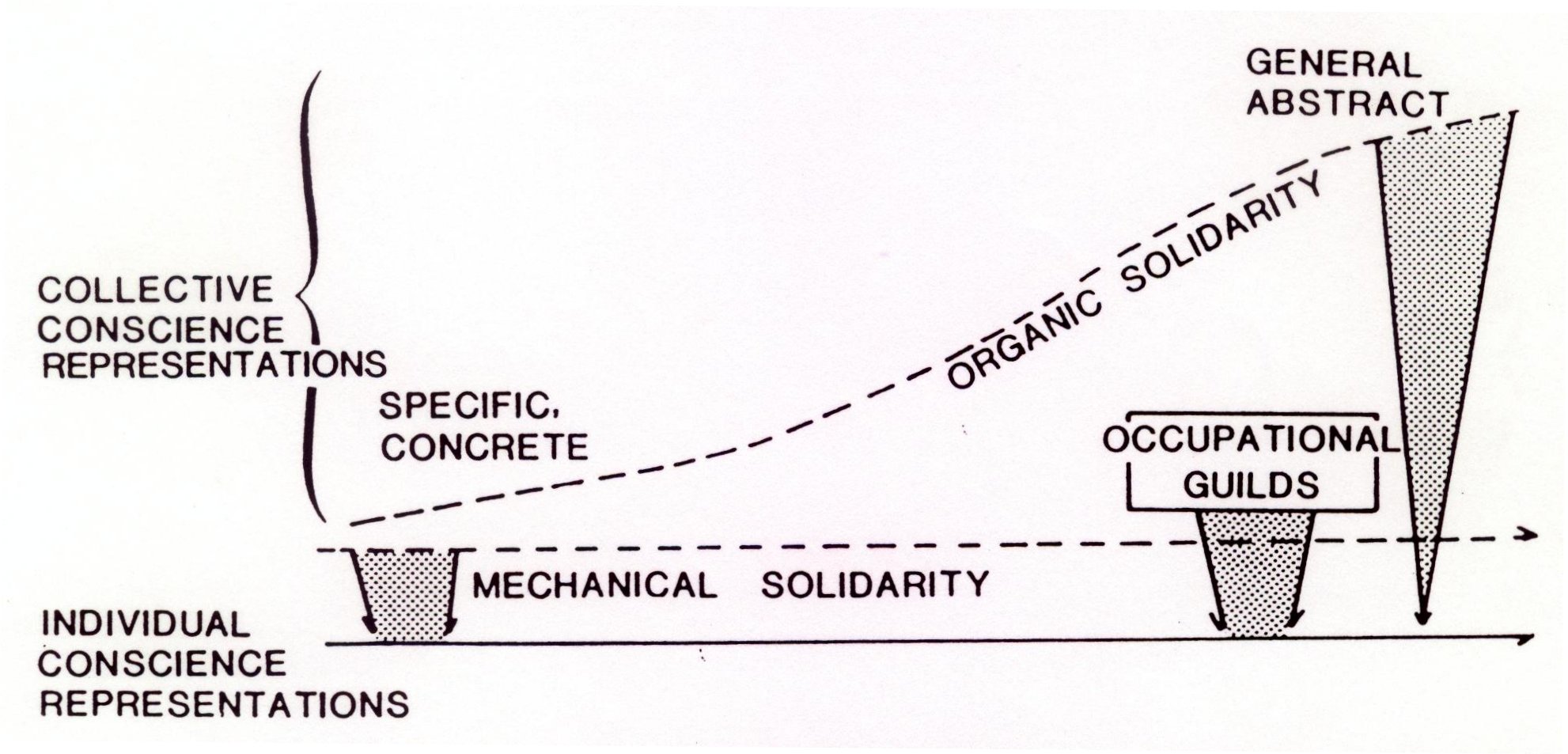

Imagine a small, rural village where life revolves around agriculture, with generations carrying on the traditions of their ancestors. In this tight-knit community, everyone shares similar values, beliefs, and practices, creating a sense of unity and shared purpose. This, according to Durkheim, is the embodiment of mechanical solidarity, a type of social cohesion where individuals are bound together by their shared beliefs, values, and customs.

In societies exhibiting mechanical solidarity, individuals are largely indistinguishable from one another, their roles clearly defined, and their lives deeply intertwined with the collective. This uniformity fosters a strong sense of shared identity and purpose, creating a powerful social glue that holds the community together.

Examples of Mechanical Solidarity in Action:

- Traditional Tribal Societies: Early tribal societies, where kinship ties and rituals were paramount, are classic examples of mechanical solidarity. The shared belief in ancestral spirits, communal rituals, and a strong sense of kinship created a network of interdependence, ensuring the group’s survival and prosperity.

- Amish Communities: The Amish communities, with their strict adherence to religious principles and traditional lifestyles, represent a modern-day manifestation of mechanical solidarity. Their tight-knit communities, where communal labor and shared religious practices dominate daily life, demonstrate the strength of shared beliefs and values in creating a cohesive social fabric.

- Small Villages: Small villages, particularly in isolated rural areas, often exhibit strong elements of mechanical solidarity. The close proximity of inhabitants, shared experiences, and reliance on each other for support foster a sense of community and solidarity, where everyone knows their place and everyone’s contributions are valued.

Organic Solidarity: Interdependence in a Complex World

As societies evolve and become more complex, the nature of social cohesion shifts from the shared customs of mechanical solidarity to the specialized functions of organic solidarity. In societies characterized by organic solidarity, individuals are held together by their interdependence, each specializing in specific roles and contributing to the overall functioning of the social system.

In contrast to the homogeneity of mechanical solidarity, organic solidarity thrives on diversity. The increasing complexity of modern life necessitates the division of labor, leading to specialized professions, diverse skills, and a greater reliance on each other for survival. This interconnectedness, while seemingly chaotic, creates a subtle but powerful form of social glue, where individuals are bound together by their mutual dependence.

Image: cupsoguepictures.com

Examples of Organic Solidarity in Action:

- Modern Nation-States: Modern nation-states are prime examples of organic solidarity. Individuals contribute to the collective good through their specialized roles – doctors, teachers, engineers, and artisans each play a vital part in the intricate tapestry of modern society. The interdependence of these diverse roles fosters a sense of cohesion, even as individuals may have very different backgrounds and beliefs.

- Globalized Economy: The interconnectedness of the global economy, with its intricate web of trade and exchange, is another manifestation of organic solidarity. Individuals in different parts of the world rely on each other for goods and services, creating a delicate balance where each participant’s contribution impacts the whole.

- Online Communities: The emergence of online communities, where individuals with shared interests forge connections across geographical barriers, demonstrates a novel form of organic solidarity. Shared passions can bind people together, building virtual networks of support and collaboration, even in a technologically mediated environment.

The Transition from Mechanical to Organic Solidarity

The shift from mechanical to organic solidarity is not a sudden event but a gradual process driven by social change. As societies evolve from agrarian economies to industrialized ones, the rise of cities, the specialization of labor, and the growth of education and technology contribute to the disintegration of traditional ways of life. This transition can be fraught with challenges, as individuals grapple with the loss of familiar customs and the emergence of new cultural norms.

These challenges often manifest in social tensions, including:

- Anomie: Durkheim posited that during the transition from mechanical to organic solidarity, individuals may experience a state of anomie, characterized by a feeling of alienation, normlessness, and a lack of purpose. This disconnect can stem from the erosion of traditional values, the rapid pace of social change, and the difficulty of finding meaning in a complex world.

- Class Conflict: The increasing division of labor in organic solidarity can lead to social stratification, with differences in wealth, status, and power creating cleavages between social classes. The disparities in resources and opportunities can fuel class conflict, potentially disrupting the social order.

- Cultural Diversity: While organic solidarity is built on diversity, navigating cultural differences can present challenges. The clash of values, beliefs, and practices can lead to misunderstandings, prejudice, and social tensions.

Navigating a World of Organic Solidarity

Understanding the transition from mechanical to organic solidarity is essential for navigating our increasingly complex world. As traditional social structures unravel, and the diversity of cultures and lifestyles grows, the challenge lies in forging new forms of social cohesion that can accommodate both our individual needs and the collective good.

Here’s how we can navigate this shifting landscape:

- Emphasize Shared Values: Even as societies diversify, there are core values that can unite us, such as respect for human dignity, the pursuit of justice, and the preservation of the environment. Building bridges based on shared values can foster a sense of community and solidarity.

- Promote Inclusivity: Creating equitable access to education, healthcare, and economic opportunities is crucial for fostering a sense of social cohesion in a diverse society. Addressing social inequalities and promoting inclusivity can help bridge the divides between different social groups.

- Embrace Digital Connectivity: While digital technologies can be isolating, they also offer unprecedented opportunities for connection and collaboration. Leveraging online platforms to build communities based on shared interests, support networks, and shared goals can foster a sense of belonging in an increasingly interconnected world.

Mechanical And Organic Solidarity Examples

Conclusion: The Evolving Tapestry of Social Cohesion

The concepts of mechanical and organic solidarity offer a powerful framework for understanding the evolution of social structures and the dynamics of social cohesion. While traditional societies relied heavily on shared beliefs and customs, modern societies are characterized by interdependence and diverse specialized roles. Navigating this transition requires a nuanced understanding of the forces at play, recognizing both the challenges and the opportunities that arise from this shift.

By fostering shared values, promoting inclusivity, and embracing the possibilities of digital connectivity, we can build bridges of understanding and cultivate a sense of belonging in an increasingly diverse and interconnected world. As Durkheim’s work reminds us, social solidarity is not simply a nostalgic relic of the past but a crucial element for navigating the complexities of the present and shaping the future of our collective existence.