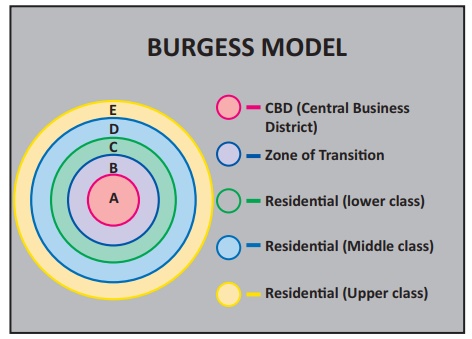

Imagine a city as a series of concentric circles, each representing a distinct social and economic environment. In the heart lies the central business district, bustling with commerce and opportunity, while the outer rings house the suburbs, offering peace and quiet. This simple visualization, rooted in the principles of urban ecology, forms the foundation of the Concentric Zone Theory, a powerful tool for understanding the spatial patterns of crime in urban areas.

Image: www.youtube.com

Developed by sociologist Robert E. Park and Ernest W. Burgess in the early 20th century, the Concentric Zone Theory provides a framework for analyzing the distribution of crime and delinquency within cities. It argues that the spatial arrangement of urban zones, driven by factors like socioeconomic status, population density, and access to resources, creates a distinct social and criminal landscape. This theory has profound implications for understanding the root causes of criminal behavior and for developing effective crime prevention strategies.

Delving into the Zones: A Systematic Approach

The Concentric Zone Theory identifies five distinctive zones radiating outwards from a central city core:

- Zone 1: Central Business District: The core of the city, characterized by commercial activity, high land values, and a transient population. While crime is present, it is often associated with property crimes and white-collar offenses.

- Zone 2: Transitional Zone: This zone is typically a transition area between the CBD and the residential areas. It is characterized by dilapidated housing, high population density, poverty, and a lack of social services. It is often associated with high rates of crime, particularly violent crime.

- Zone 3: Working Class Zone: This zone is a more stable residential area with a mix of blue-collar workers and modest homes. While crime rates are lower than in Zone 2, they are still higher than in outer zones.

- Zone 4: Residential Zone: This zone typically consists of single-family homes, higher income residents, and lower crime rates.

- Zone 5: Commuter Zone: The most affluent zone, characterized by low population density, large estates, and minimal crime.

The Social and Economic Drivers of Crime

The Concentric Zone Theory argues that the unequal distribution of resources and opportunities across these zones directly influences crime rates. Zone 2, the transitional zone, is often considered the epicenter of crime, due to its unique constellation of social and economic factors:

1. Poverty and Economic Deprivation:

High rates of poverty, unemployment, and limited access to education and job opportunities in Zone 2 create a breeding ground for criminal behavior. The lack of economic prospects drives some individuals to engage in illegal activities to meet their basic needs, while others may turn to crime due to feelings of frustration and resentment.

Image: www.brainkart.com

2. Residential Instability and High Population Density:

High turnover rates, dilapidated housing conditions, and overcrowding contribute to social disorganization and a breakdown in social control mechanisms. In this chaotic environment, residents may have limited trust in their neighbors and institutions, making it difficult to establish strong social bonds that discourage crime.

3. Cultural Transmission of Crime:

The concentration of marginalized and disadvantaged individuals in Zone 2 can foster the transmission of criminal values and attitudes across generations. Children growing up in this environment may be exposed to criminal behavior from an early age, making them more likely to adopt these behaviors themselves.

Beyond the Zones: The Limits of the Theory

While the Concentric Zone Theory offers a valuable framework for understanding crime patterns in cities, it has limitations. It focuses primarily on spatial factors and neglects other social and economic forces that contribute to crime. Additionally, contemporary cities are increasingly complex and diverse, with social and economic boundaries often blurring, making a simple concentric model less applicable in some cases.

Furthermore, the theory has been criticized for its deterministic view of crime, implying that residents of certain zones are inherently predisposed to criminal behavior. Critics argue that socioeconomic factors may influence criminal behavior, but they do not predetermine it. Other theories, such as the Strain Theory and the Social Learning Theory, offer alternative explanations for why individuals engage in crime that challenge the deterministic nature of the Concentric Zone Theory.

Concentric Zone Theory Criminology

The Enduring Relevance of the Concentric Zone Theory

Despite its limitations, the Concentric Zone Theory remains an important framework for understanding the spatial patterns of crime in cities. It highlights the crucial role of social and economic factors in shaping criminal behavior and provides valuable insights into the challenges faced by marginalized communities. The theory continues to shape urban planning and crime prevention strategies, emphasizing the need for addressing the root causes of crime by promoting economic opportunities, improving housing conditions, and fostering strong social connections in disadvantaged neighborhoods.

Understanding the dynamics of urban zones through the lens of the Concentric Zone theory can provide a roadmap for creating more equitable and safer cities for all citizens. It encourages us to look beyond superficial crime statistics and delve into the complex social realities that create and perpetuate crime in our communities.

This examination of concentric zone theory in criminology highlights the multifaceted nature of crime in urban environments. It reminds us that understanding the historical context, social structures, and economic inequalities that contribute to crime is vital for developing effective solutions to this complex social phenomenon. By examining these issues, we can strive to create safer and more just cities, where everyone has the opportunity to thrive.